Current Location

(enter callsign KG6NNZ)

Logbook: March 4-5, 2007 - Panama Canal Transit

We arrived in Panama City in early February, and shortly thereafter, we started making the arrangements for Slip Away's transit of "the big ditch."

|

The process was actually quite easy. First, we visited the "Admeasurers Office" where we filled out some paperwork. All of the forms we needed to fill out were in English, and most everyone at the office spoke English. A couple of days later, the Admeasurer came out to Slip Away to measure her length. (Normally, this happens the next day, but we were delayed a day due to the Carnaval celebration.) The Admeasurer was an American who had been living in Panama for the past 30 years, and he measured Slip Away from the tip of the anchor on our bow pulpit to the end of our mizzen boom, which is the point that stuck out furthest on our stern since we were putting the dinghy on deck and folding in our dinghy davits. Although Slip Away is a 41' boat, she measured out to be 47', which was fine with us. Boats under 50' are charged $600 for a transit; over 50', the cost is $800. The next day, we went to the Citibank branch in Balboa to pay for our transit, and that evening, we called the scheduling office and requested a transit date of Sunday, March 4. |

|

Canal regulations required a captain and four line handlers on board, so we needed to secure some additional crew for our transit. Jan agreed to let Rich be the Captain and drive the boat. Since it was important to provide good meals and snacks for the Advisor and crew, and we wanted good photos of the transit, Jan relinquished line-handling duties and volunteered to be galley wench and trip photographer. Our cruising friends Pat & Carrie from Terra Firma and Iain & Aly from Loon III volunteered to line handle for our transit, as well as our friend Chris Miller who flew in from Virginia. We had more crew than we needed, but we had enough room for everyone, and we figured it's always good to have an extra hand around. We also needed some additional equipment - lines and fenders. We rented lines from the Balboa Yacht Club - four 150' 5/8" lines, which were specified by canal regulations. For fenders, we collected 20 old tires wrapped in garbage bags and tied them along the port and starboard sides of our boat. Tires are used as fenders by most pleasure yachts during transits and are passed on to each other as transits are completed. There are usually a surplus of tires on the Panama City side of the canal (where we were), so we got the tires for free. Folks on the Colon side sometimes have to buy the tires ($3 each). Finally, we wanted to get some experience before taking our home through the Canal. It's highly recommended to go through the canal as a line-handler on someone else's boat before taking your own through. A few days after we arrived in Panama City, Rich was able to get a line-handler position on "Moira" (a boat we met at Catalina Island in California), but they didn't have enough room to take both of us. Fortunately, about a week later, "Time Machine" (friends we met in El Salvador) asked us both if we could line-handle for them. The experience we gained on Moira and Time Machine was invaluable. |

|

Background Info on the Panama Canal

The feasibility of building a canal through the isthmus of Panama was first studied in the 1500's. During Spanish Colonial times, extensive cobblestone mule trails were paved across the isthmus, and tons of gold from Peru traveled over these trails on the way to Spain. In the 1850's, the Panama Railway was constructed, and it was a very successful venture. In 1879, a French company was awarded the exclusive rights to building a waterway across the isthmus of Panama. They spent $285 million U.S. dollars and lost 20,000 lives trying to build a sea-level canal. Diseases and harsh geographic and climatic conditions, as well as fiscal mismanagement, contributed to the failure. In 1894, a second French company recommended construction of a lock-type canal, but they were unable to secure financing and went bankrupt. The second French company sold the Canal equipment, as well as all rights and ownership to the U.S. government. At this time, Panama was a part of Columbia, and FDR was President of the U.S. President Roosevelt did not have a very positive opinion of Columbia's government and encouraged Panama's secession from Columbia.

In 1903, Panama declared independence from Columbia, and shortly thereafter, Panama and the U.S. signed the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty, by which the U.S. undertook the construction of a canal across the isthmus. The builders faced huge obstacles, but the Canal was completed in ten years and opened to traffic on August 15, 1914. It cost almost $400 million to build and utilized the labor of more than 75,000 workers, but it was completed below estimated cost, earlier than projected and without a hint of corruption. Since then, there have been more than 850,000 transits through the waterway. An aggressive maintenance program keeps the Canal in top operating condition. On December 31, 1999, per the Torrijos-Carter treaty signed in 1977, the U.S. turned over ownership and operation of the Panama Canal to the Republic of Panama.

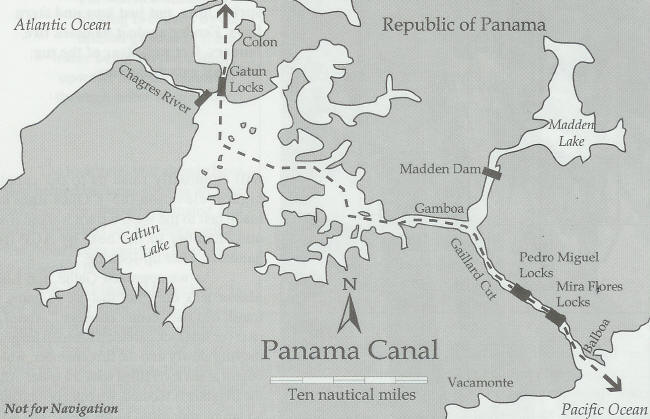

The Canal was carved through one of the narrowest and lowest points of the mountainous isthmus of Central America. The isthmus of Panama runs east-west; the Pacific entrance to the Canal is on the south side of the isthmus at the port of Balboa (near Panama City), and the Atlantic entrance is on the north side at the port of Cristobal (near the city of Colon). There are two sets of three locks on the south side and two sets of three locks on the north side, and the locks are connected by Gatun Lake and the Gaillard Cut. Gatun Lake was formed by building a dam across the Chagres River. When the Canal was built, Gatun Dam was the largest earth dam ever built; Gatun Lake was the largest man-made lake; and the locks were the largest concrete structures in the world. The Gaillard Cut was carved through the Continental Divide. Fifty trainloads of rock and soil were removed every day during the height of the excavation through the Continental Divide. There is presently a plan in place to build a third larger set of locks and widen the Gaillard Cut to accommodate larger ships. The Panama Canal expansion is scheduled for completion in 2014, which is the same year that the Panama Canal will celebrate its 100th birthday.

Since we were transiting the canal from the Pacific to the Atlantic, we were doing a "northbound" transit. We "up-locked" in the two Miraflores Locks, crossed Miraflores Lake (just under a mile), and then up-locked in the Pedro Miguel Lock. We then motored 7.4 miles through the Gaillard Cut and 20.4 miles across Gatun Lake. After spending the night in Gatun Lake, we "down-locked" in the three Gatun Locks to complete our transit.

For more information on the Panama Canal, the website is www.pancanal.com. We'd also recommend David McCullough's 600+ page book, The Path Between the Seas, which is a very informative history of the canal and a good read. For cruising boats considering a canal transit, we found David Wilson's A Captain's Guide to Transiting the Panama Canal in a Small Vessel to be extremely helpful.

Our Transit

|

We had a very good transit of the Panama Canal - it didn't go perfectly, but it went well, and we made it safe and sound. We started our Panama Canal transit on Sunday (March 4), spent the night in Gatun Lake, and finished our transit on Monday (March 5). Our canal transit got off to an interesting start early on Sunday morning. Our line handlers arrived at Slip Away about 7 a.m., and we were instructed to call "Flamenco Signal Station" on our VHF radio at about that same time to get our advisor boarding time. When we called Flamenco Signal, they initially told us our advisor would board Slip Away at 8:10. About 20 minutes later, they called us back and told us our transit was canceled and that we were rescheduled for the next day - no reason given. As we were sitting in the cockpit getting over our disappointment and deciding what to do with the day, Flamenco Signal called back again and said they found an advisor for us and that he would board at about 9:00 (he was coming from Colon, which is about 1½ hours away). Big smiles all around! (We can only surmise that the advisor originally assigned to us called in sick.) |

|

|

Our advisor, Meza, boarded Slip Away about 9:30, and we started motoring toward the first lock. As we passed under the Bridge of Americas, our engine raw water flow alarm went off. $#&*%!! We looked over the side of the boat, and there was no water coming out of the exhaust. Rich had changed the raw water impeller just a couple months ago, so we didn't expect that it would fail. The engine was starting to overheat, so we pulled over to the side of the channel, dropped the anchor and shut the engine down. Rich was frantically trying to figure out what was wrong. When he checked the raw water strainer, there was water coming into it, and Iain calmly suggested that we try to start the engine again - maybe we had sucked a plastic bag against the intake. We started the engine, and everything was fine - apparently we had sucked something over the intake, and when we shut down the engine, it floated away. We always hear about this happening, but in the 5 years we've had Slip Away, this is the first time it has happened to us. What a way to start our transit!! We up-locked in the two Miraflores locks tied to a tour boat, which was tied to a tug, which was tied to the sidewall, and we were behind a big freighter. The freighter stopped and anchored after Miraflores, and we up-locked in Pedro Miguel with just the tour boat. All of the tourists were taking photos of us, and we were taking photos of them. We exited the Pedro Miguel Locks at about 12:45 p.m., and our advisor told us we needed to get to the Gatun locks by 4:50 p.m. to make our scheduled down-lock time. To get to the Gatun locks, we needed to motor through the Gaillard Cut and across Gatun Lake, a total distance of over 25 miles. Timing would be close, but we thought we could make it. Slip Away ran at about 6.5 knots most of the way, except when the headwinds got over 20 knots, and then she slowed down to around 6. As we got closer to the Gatun locks, Meza radioed ahead and told the pilot on the freighter with which we were to down-lock that we would be there, and he asked him to wait just a couple of minutes to let us get into position first. We arrived the Gatun locks at 4:47 p.m., but the freighter did not wait for us and was already going into the lock, so we had to spend the night in the lake. Meza was frustrated with the pilot on the freighter, but we were looking forward to spending the night in the lake. We really liked Meza - he was a good advisor and very friendly. "Cristobal Signal Station" told Meza that we should expect our advisor for down-locking at about 2 p.m. the next day. |

|

A pilot boat came and picked up Meza, and we opened a bottle of champagne to celebrate a successful first half of our canal transit. That evening, we enjoyed a lasagna dinner and settled in for the night. We managed to find (relatively) comfortable places for everyone to sleep - in the v-berth, the cockpit and the salon, and Carrie even slept a few hours in her hammock, which was hung up on our front deck. It was a calm and quiet evening with the exception of a few howler monkeys roaring in the jungle, and another cruising boat arriving to share our mooring at about midnight.

|

The next morning, we called "Cristobal Signal Station"

about 9 a.m., and the plan changed - they told us our advisor would be at Slip

Away at about 10 a.m. (Good thing we called early!) Guillermo showed up at

10:30, and we down-locked in the Gatun Locks center-tied in front of a freighter. Guillermo, too,

was a good advisor and very friendly. When we exited the final lock, it was blowing 20-25 knots on our nose, and although there wasn't a swell, there was some pretty good wind chop on the water. When we dropped Guillermo off at the pilot boat, they drifted into us, and we hit pretty hard. Slip Away took the impact well, with the exception of a new crack in our teak cap rail. Fortunately, that's easily repaired. Also, it's not the only crack in the caprail, but at least this one has a good story to go with it! After anchoring Slip Away in "The Flats," we popped open another bottle of champagne, celebrated our successful transit and enjoyed lunch. We then dinghied our friends Pat & Carrie and Iain & Aly into the Panama Canal Yacht Club dock so that they could catch a bus back to Panama City. We were very choked up and teary-eyed as we said good-bye. We'd spent the better part of this past year cruising with these folks, and they became very good friends. |

|

And now, we and Slip Away are off to explore a new ocean.